The impact of AI on UK FOI requests

The impact of AI on UK FOI requests

For a while now, I’ve noticed a steady increase in FOI requests that appeared to me to have been written almost entirely by AI. This weekend, I thought I’d look into this a bit using machine learning and some linguistic analysis. I’ve now looked at more than one million FOI requests submitted via WhatDoTheyKnow, and discovered some things that I found interesting.

Building the AI Detector

To try to find out the scale of AI usage, I started out by building a custom AI detector that is tailored to find AI written FOI requests. I fine-tuned a DistilBERT model on a dataset of ~51,000 requests. This included ~38,000 human-written requests from the early years of WhatDoTheyKnow (long before generative AI tools were available to the public) and ~13,000 synthetic requests that I generated for this purpose.

Most of the synthetic requests were created using GPT 4o, as it has a very distinctive “voice” that I had seen the most often, and was widely available for free during the time period over which I first noticed the changes in language. To add a bit of diversity, the dataset also included some outputs from Mistral Nemo, which is good at mirroring a GPT-3.5 like style and GPT-5 to capture more recent patterns. After three epochs of training, the model achieved near-perfect accuracy on the evaluation samples (around 12,500 examples) which I was quite suspicious of.

I decided to run the model on more than 1,000,000 requests that I had scraped from WhatDoTheyKnow. By scanning all the way back to 2008, I could start to establish a baseline for false positives and gain more understanding of the reliability of the tool when looking at real world data. Of the 770,000+ requests from the pre-GPT era, 99.9% were correctly identified by the classifier model as having been created by humans. This far exceeded my expectations.

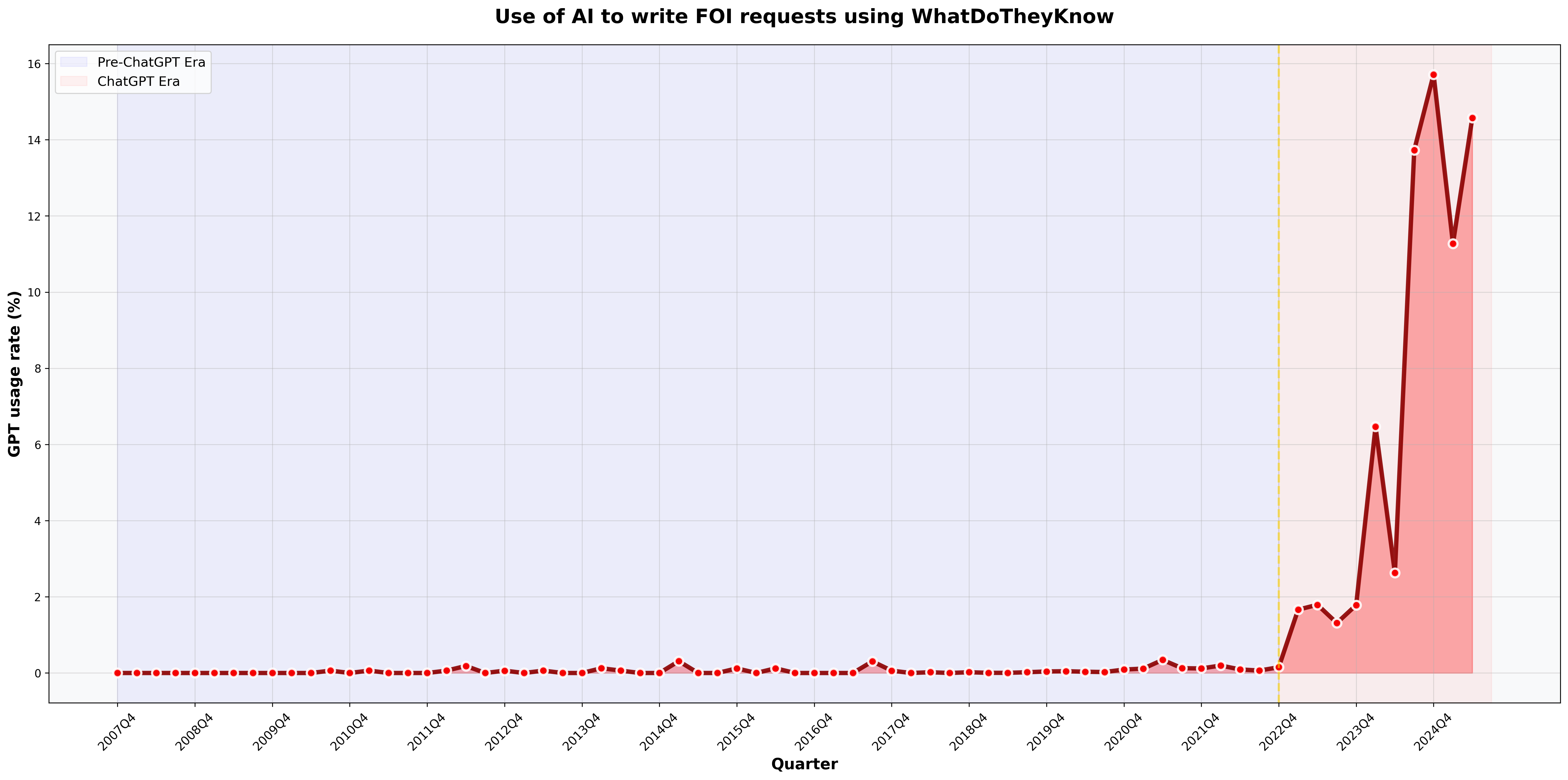

When the results of the classifier are plotted by quarter, it is immediately clear that the use of AI to generate FOI requests appears to be becoming more widespread.

AI written requests would seem to account for a significant and growing proportion of requests that are made using WhatDoTheyKnow.

Generally, the model answered with a very high degree of confidence. Where the confidence level was lower, the requests seemed to contain elements that are consistent with generative AI, and may have been more extensively edited. I would like to do more work to understand the limitations of the classifier. I do not yet know if it is only able to detect the stylistic quirks of ChatGPT, or would also detect texts from other AI models such as Claude or Gemini. I am also curious to see how much editing you would need to do to an AIrequest before the classifier would consider it to be human-written.

The fingerprints of AI

As I have mentioned in previous posts, OpenAI’s models tend to write requests full of unnecessary “slop” and filler. The outputs contain phrasing that looks like the sort of thing that belongs in a request, meaning that those who generate requests in this way often don’t edit it out. These are phrases that regular requesters who write their own requests would not naturally include, which makes these features a clear fingerprint of AI. Beyond that, there are further differences between AI and human-written requests that I think are worth looking at in more detail.

The rise of copy paste

WhatDoTheyKnow uses a standard request template that has remained largely unchanged over the past 17 years. For most of that period, it has started with “Dear [Public Authority]” and ended with “Yours faithfully, [Requester Name].” Typically, the site’s users do not alter the start and end of this template, with ~94% of all requests sticking to it, a figure that remained steady over time.

Since ChatGPT was launched however, something has changed. The number of requests that are signed off with “Yours faithfully” has started to decline. At the same time, alternative sign-offs favoured by AI are increasing. By the end of H1 2025 (January to Jun 2025), use of “Yours sincerely” has increased by 210% on the pre-GPT baseline (pre-Dec 2022), and “To whom it may concern” has increased by 265%. Use of the standard template fell to 92% of requests in 2023, dropped further to 89% in 2024, and was 86% in the first half of 2025. I anticipate that we will continue to see this fall.

This is a strong indication that users are copy-pasting complete requests directly from AI, and in many cases fully overwriting the standard template. The percentage of requests overriding the template in some way has more than doubled since the arrival of ChatGPT. I even found a number of examples containing unedited AI placeholder text in square brackets.

“GPT-isms”

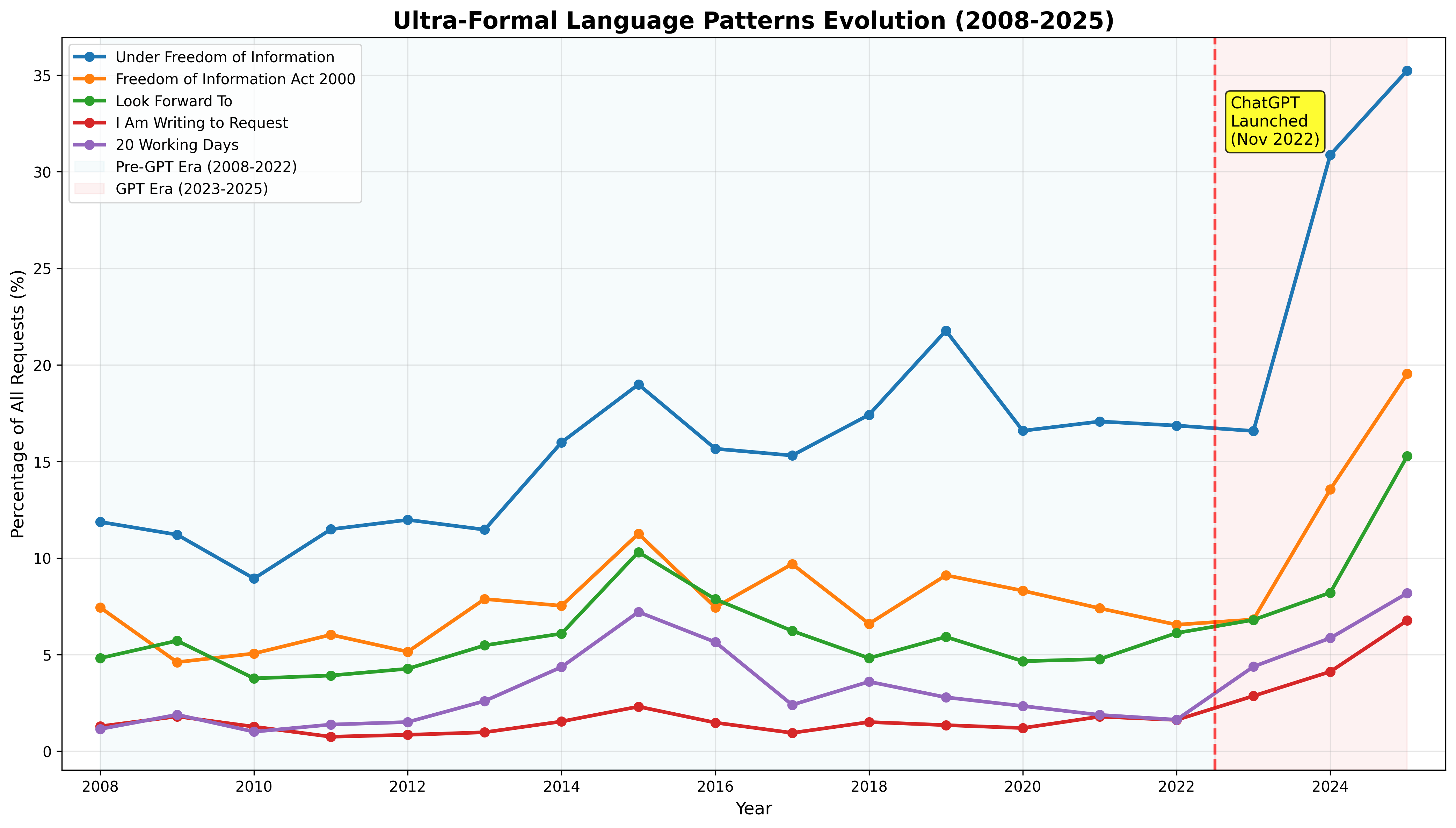

There are specific phrases and stylistic choices that large language models seem to love that have seen significant growth in recent years. These “GPT-isms” make new requests sound overly polite, overly formal and overly legalistic (I too can write in triplets).

The phrase “statutory timeframe,” which appeared in just 0.02% of requests from 2008-2023, appears in 2.1% of requests in H1 2025, an increase of 13,380%. There has also been a spike in excessive politeness from the baseline figure including “thank you for your consideration” (2,238% increase) “I hope this message finds you well” (5,091% increase). “Thank you for your time” could be found in (in 9% of requests in H1 2025, a 776% increase).

There are several more “tells” that I have seen, and that commonly appear in requests that are flagged by the AI detector. All increases mentioned below are from the pre-GPT baseline to H1 2025, though in most cases, their usage also grew in 2023 and 2024.

- Starting the request with a sentence stating that you are making a request e.g. “I am writing to request” (~400% increase), I am submitting (1333% increase) or “I hereby request” (31% increase). This feature is found in 93% of requests that were flagged as being by GPT.

- Mentioning the “Freedom of Information Act 2000” (252% increase). This also appears to be occurring in requests to Scottish Authorities which are not in fact subject to that specific Act.

- Explaining what the aim of the request is (not something the requester is required to do).

- Using the word “specifically,” followed by a list or series of lists of information types (209% increase in the use of “specifically”).

- Using headings above numbered lists.

- Pre-emptively asking for an explanation of exemptions that might be applied or mentioning clarification (143% increase).

- Mentioning expecting a response or saying that the requester will “look forward to your response” (704% increase) within “20 working days” (108% increase) or “statutory 20 working days” (248% increase).

- “Broad requests requesting “all documents” or “any and all” documentation (106% increase).

- Asking for 5 years of data (this has more than doubled).

- Asking for a “breakdown” (166% increase) or saying “broken down by” (155% increase)

- Specifying financial or ‘fiscal’ years for data that would be held in calendar years or academic years (51.8% increase in “financial year”).

- Inclusion of a subject line in the body of the request starting with “Subject:”.

- Including a list of years in brackets, such as (2020/21, 2021/22, 2022/23). This feature is almost entirely absent from pre-GPT requests, but it looks like it makes things clearer, so I can see why humans like to leave it in.

- Including excessive and unnecessary examples, usually as collections of three or five things - (218% increase in the use of e.g.)

- Using punctuation in a hyper correct way, such as “(e.g.,” (24,750% increase and now present in 5% of requests).

- Asking for a receipt or acknowledgement of receipt

- Asking for a reply to the “email above”.

Further structural signs

Beyond the linguistic signs/tells referenced above, AI-generated requests can also be spotted by their structure. The requests that I generated to train the classifier model are substantially longer than human-written requests, and this was also reflected in the length of requests on WhatDoTheyKnow that were flagged as AI. The mean word count of those requests is 249 words, compared to 135 words for human requests from the pre-GPT era and 160 words for contemporary requests that are identified as being written by humans. This is an 84% increase in length over the historical baseline. AI requests contain more than double the number of sentences on average. There was also a sharp increase in the median word count that perfectly coincides with the introduction of GPT.

What does this mean?

Whilst I would caution that correlation does not equal causation, so far the evidence appears to be compelling. The changes in linguistic patterns consistently track the introduction of generative AI. The fact that these fundamental changes also align neatly with my tenure as WhatDoTheyKnow’s service manager on the other hand, is clearly coincidental.

The widespread availability of LLMs appears to have fundamentally altered how people are interacting with the state when making FOI requests, and it is unlikely to ever return to how it once was. We are seeing requests becoming longer, more formal, and also more homogenised. This is perhaps unsurprising, as instead of a wide range of voices, we are now hearing the voice of a single ghostwriter start to drown out the rest. It is unclear what impact this will have on human curiosity, and if the increased standardisation will lead to a narrowing of the range of things people ask for. I would not welcome such a change.

Whilst the requests that are generated look good, if we are not careful, these may start to place a greater burden on public authorities, who have to process requests that are longer, broader and more complex than what we have typically seen in the past. I have started to see the first rumblings of this in the notes on the KPI dashboards and performance reports for some local councils. Like much of the public sector, they are already under-resourced. The apparent AI default of asking for five years of records could impose significant additional costs relative to the one to three year period that would in my experience be more typical for a human-written request.

I am worried that new requesters will think that they need to be able to write like this to make a request, and will be put off from trying. This fear was a key motivator behind my recent experiments with developing my own bespoke request writing model from scratch. If people are going to use these tools, and the evidence is that they already are, I would like to help them to write good ones. My models are trained to avoid most of the issues found above, although this remains a work in progress. It can be done.

I remain sufficiently curious about this issue to want to keep working on it. In some ways, it has raised more questions than it has answered:

- What is going on with internal reviews? Are these longer or more common on AI written requests? The council data hints at this too.

- Are the AI-generated requests more or less likely to be successful? Are they asking for information that isn’t held at a higher rate?

- Are these being made by first time requesters, bot farms or experienced users who want a bit of help polishing the requests?

- Is there less diversity in the topics of the AI requests compared to standard ones?

- Do the requests reflect what the user actually wanted or what the AI told them to ask?

- Can I get a small generation model working to the extent that it is safe to deploy somewhere? Could a custom GPT be just as effective?

I will end by saying that this has made me start to see the value of the archival data in a new light. Pre-GPT data is the new low-background steel and carries greater value than ever before.