WhatDoTheyKnow Wrapped

I’ve been reflecting a lot recently on the time I’ve spent helping to run WhatDoTheyKnow, first as a volunteer and then as an employee, as is common during life transitions. To help me contextualise things, I asked for a copy of some of the data that has been logged in the system about my own account over the years. Some data from the early years is missing, so it looks like the logging changed around 2013. No matter, I am grateful for what I have, as it was more than enough to gain some needed perspective on what I have achieved.

What the data doesn’t show

When reading the data below, you’ll need to keep in mind that there are gaps in the data, and that what data there is covers only a small fraction of what the work actually involves. The site logs capture certain types of interactions with the software. They don’t cover admin actions taken against user accounts, data from deleted requests, or the meetings, emails, wiki edits, categories created, tables extracted, Slack posts, research undertaken, files uploaded, data gathered and cleaned, proofreading, presentations given, guides, policies, help pages and blog posts written, opening and closing GitHub issues, statistical analysis, coding, building tools, breaking tools, finding and adding citations, finetuning AI models, dataset generation, testing, and the rest that has happened over the years. A full list would be impossible.

The numbers

Based on the data here, in total, as a volunteer, I have given mySociety the equivalent of 288 working days of my time. When you take into account what is not logged, the real amount will certainly be substantially higher.

By combining my data with the public event history logs, I can see that I’ve helped a minimum of 33,442 unique users over the years. That’s not the real total of course. I have sent tens of thousands of emails, many offering advice and guidance. This work is impossible to quantify, yet has always been by far the most rewarding part.

I have added at least 16,311 new public authorities, and made updates to the data for at least 34,724 (that’s 74% of the total). To get a complete figure of those I’ve helped, I’d need to add the thousands of people who were able to make a request because of this work, and those who reused the data that was released, or read and wrote the stories and reports based on that.

Of the more than 100,000 FOI requests that I have classified, 33% were successful, 24% partially successful, 18% not held, and 10% rejected. The FOI correspondence I classified contained over 62 million words, not including attachments. That’s the equivalent of reading and categorising many hundreds of novels. I have always enjoyed doing this, and it has recently been suggested that I should put this on my tombstone. This was the very first one.

I have edited at least 4,793 requests, and 1,170 attachments. I have battled Alaveteli with several thousand censor rules, largely to anonymise PDFs and accounts. This is the most incomplete dataset of them all, but I can honestly say that I never want to write another regular expression again.

Time

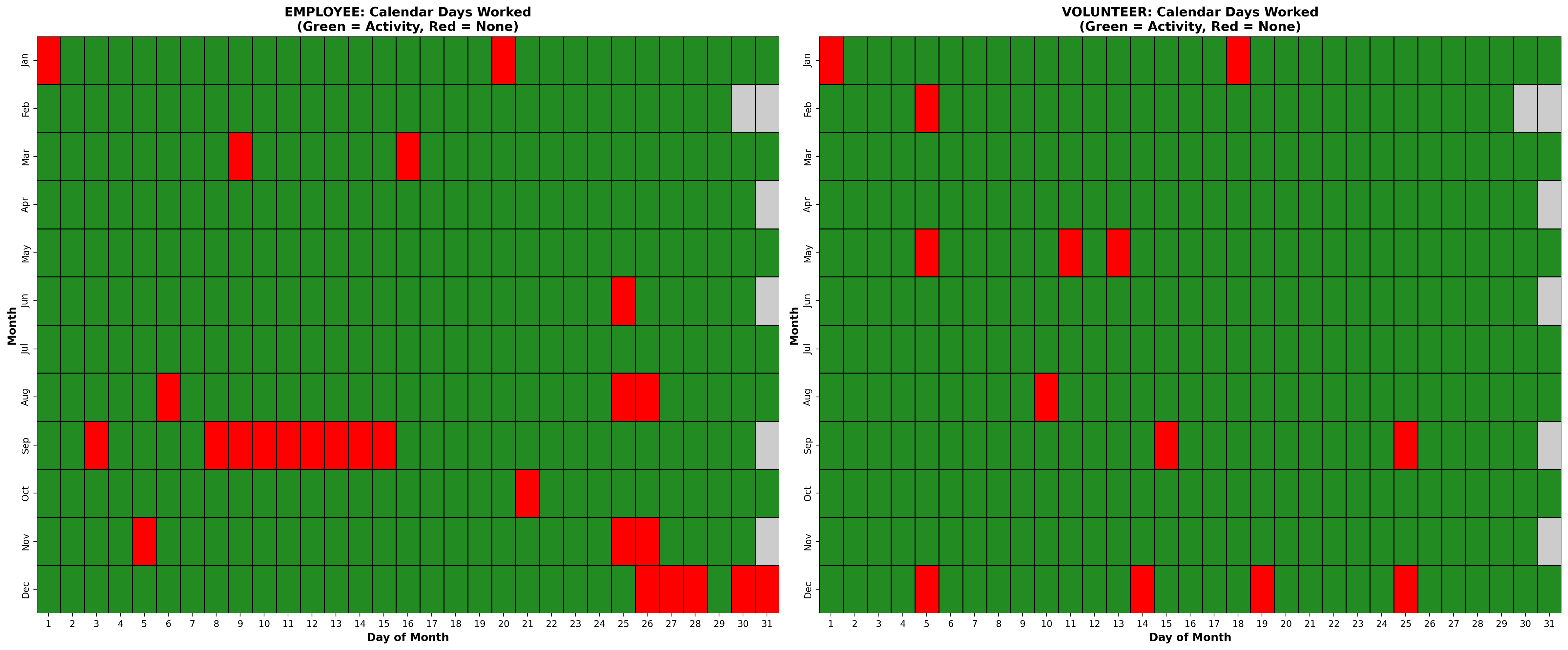

Looking at days that I worked/volunteered on across all the years covered, there were only two calendar dates with no recorded activity at all - 1 January and 15 September. I am glad to have bagged 29 February!

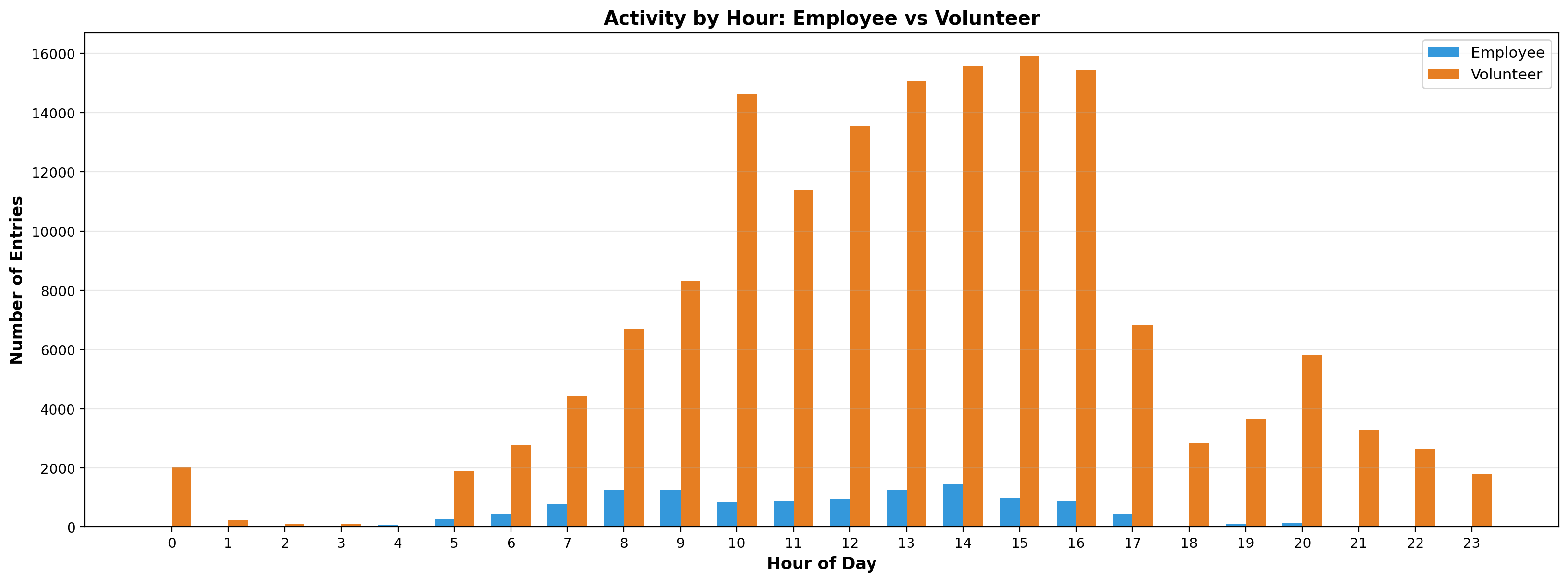

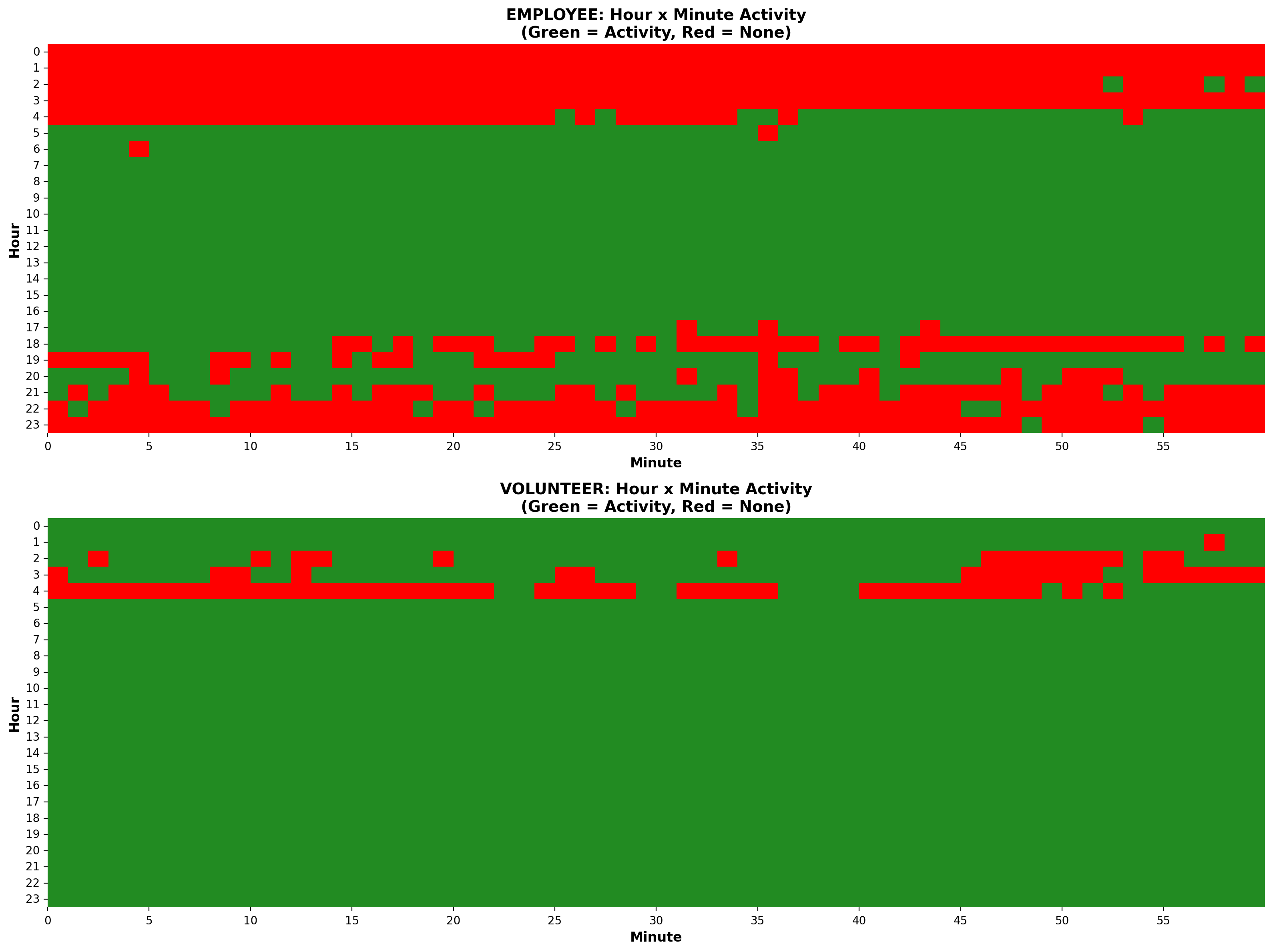

When I made the switch from volunteer to employee, I struggled to cut back the time I was putting in. This was a habit I brought with me rather than something that the role necessarily demanded. The data shows that 46% of the logged non-classification timestamps fell outside of mySociety core hours, and 32% outside of my usual flexed hours. There was even work logged on 20% of all weekend days. This significantly improved when my boss started checking in about this every week, serving as a valuable counter to my habitual stubbornness. My volunteer hours were similarly varied.

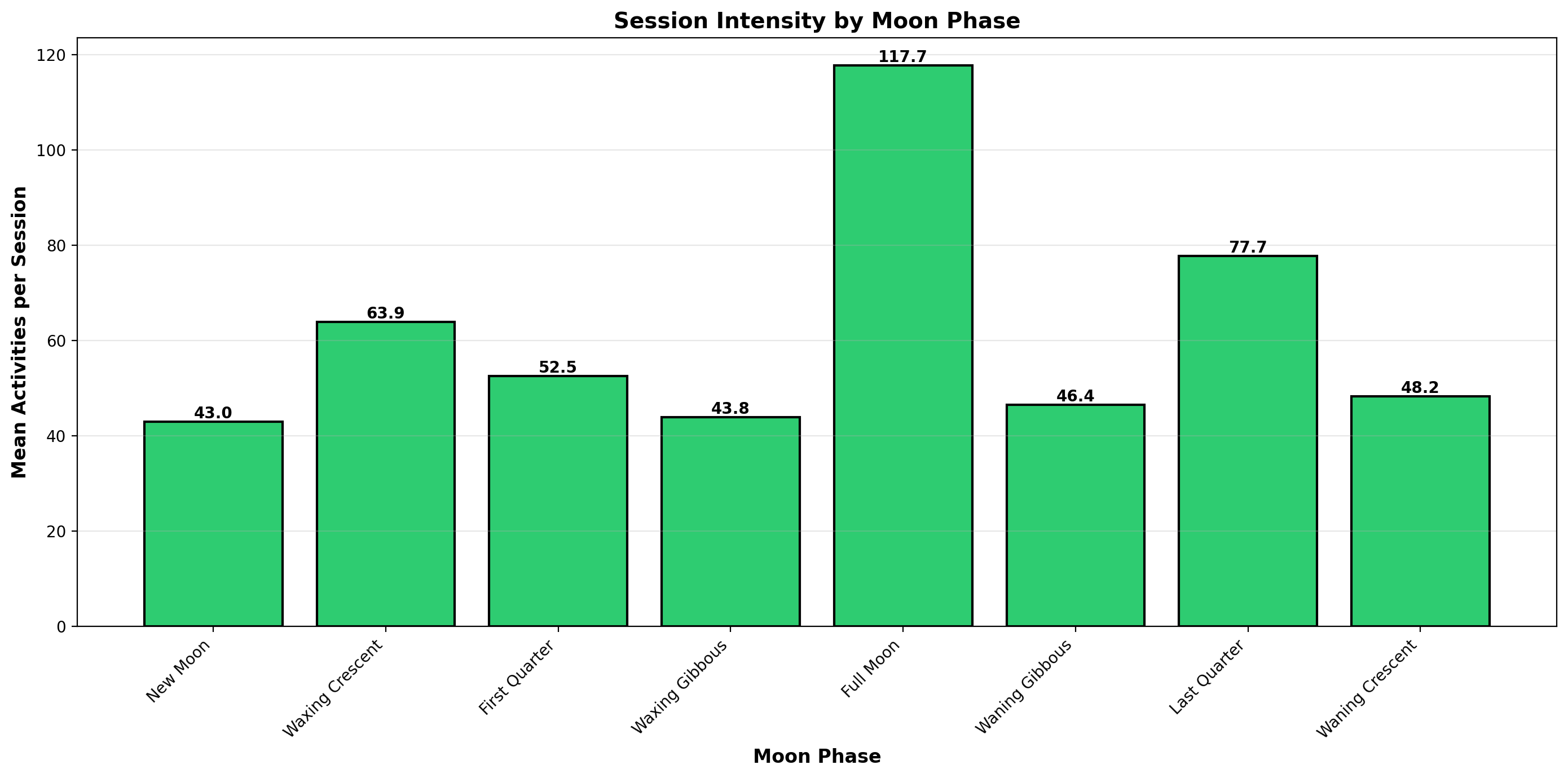

Moon fans will be glad to know that I am most active on a full moon. I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether that’s down to struggling to sleep when it’s light outside, or being part-werewolf.

The work that mattered most

Then there are the people whose data I removed following data breaches by public authorities. I don’t know whether to count these people as those I helped or those I have harmed. Finding deeply private data always felt uncomfortable, like a second violation, and I can’t honestly say if I personally did enough to highlight this issue. Ultimately that will be for others to judge.

The most significant timestamp in the data is perhaps 2023-08-08 16:27, when I deleted the response from PSNI that echoed around the world. This crystallised a long-held fear of mine of “what if?”. Perhaps my proudest achievement in post came after that, when I painstakingly checked over 13,000 spreadsheets for what should never have been there. Tooling that I built made that possible, and subsequently enabled automated checks to be put in place that now silently run in the background, preventing further harm. What happened with PSNI couldn’t happen in the same way now, making this perhaps the most significant piece of work that I will ever do. It will always feel worthwhile, though it came at a cost.

My second proudest achievement was teaching an AI model to spot personal immigration correspondence to a high enough degree of accuracy to help protect thousands of people’s information that they themselves had posted. Perhaps they didn’t understand the risk, or perhaps they were in such desperate need of help amidst a broken system that they did it anyway. It would need a minor adjustment to run as well now, as the rise in first person language in GPT-written requests may cause more false positives than you’d find with exclusively human-written ones, but regardless, that work of protecting people’s data cannot be undone.

The edit actions for both of these events were applied in bulk, so sit outside the scope of things logged against my accounts. They are significant enough to me, to note here nonetheless.

AI classification

More recently, I gave one of the lightweight Gemini models the task of classifying several thousand redacted FOI responses as a personal project to see how it would do. I tried to teach it to think like me. I can finally see just how accurate it was by comparing it to the outcomes of my manual classification, providing you accept my judgement as accurate, that is.

The model struggled with bureaucratic nuance, and was not able to reliably distinguish between requests that were successful and partly successful. In terms of identifying that some information was released and one of those two statuses applied, it was accurate 94% of the time. It achieved 95% accuracy when identifying requests for clarification, 97% accuracy for waiting response/acknowledgement only, 87% accuracy for refusals, and 88% for not held. This is based on 16,267 requests. I didn’t run it on responses with attachments, which is most of them these days, so whether you could reasonably use it for this task remains to be seen. I might have a go at pushing the bounds of what is possible, now that I have a large labelled dataset to work with, if for no other reason than to satisfy my own curiosity.

Reflections

I have always been just one of many volunteers. I’m not sure I can claim to be the most dedicated, impactful or active one. There are others that I would put ahead of myself in all of those categories. I can say that without their support, the job part would have been significantly harder. If you were to try to total up the figures for all of us, as I have done for myself, I can’t imagine what numbers you’d reach. I wish I could have supported them better.

What I can say is that this has brought me great joy and real pain over the years - sometimes both on the same day. It was never dull, occasionally surreal, and often deeply meaningful. The post-PSNI period almost felt fated, if you will allow me such a thought. As if the universe was, in its own way, nudging me to finish what I started.

Some of it may last, some of it will not. But it mattered to me, and that’s enough.